18 March 2019

As the Government is poised to extend the use of vessel monitoring systems (VMS) across the inshore fleet in England, recent experience with electronic monitoring systems (EMS) illustrate two very different trajectories for fisheries management.

Enforcement

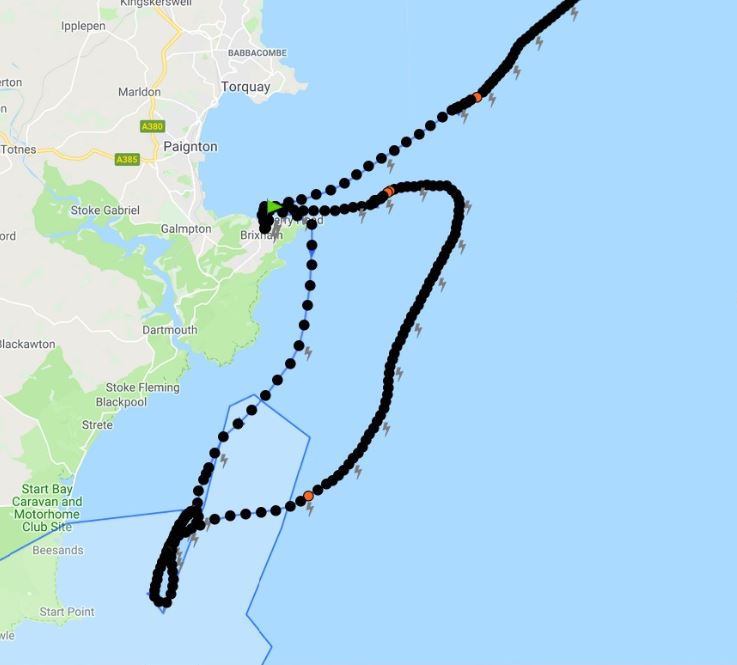

One trajectory, characterised by prosecution cases based on VMS evidence conjure up images of enforcement officers sat at computer screens picking out rule breakers in a space invaders style game without the need to leave the comfort of a padded office chair.

Undoubtedly, while many see electronic monitoring as a boon in aiding the prevention of unlawful activities and ensuring they are brought to justice, in the case of VMS it is not the same as a visual inspection of wrongdoing. The data shows only position, speed and heading, not whether illegal fishing is taking place. It, therefore, needs to be corroborated, not used as a foregone conclusion of an offence, whether to secure a prosecution or to trigger a fixed administrative penalty. Without this, there is a risk of false prosecution.

There are numerous legitimate reasons why a vessel may need to be in a management area and making headway at a similar speed to that when fishing; avoiding tide, weather or shipping, waiting for a closed area to open, dealing with a breakdown, or simply just resting, to name but a few. Until additional technology that can verify whether fishing activity is taking place is introduced, these are the limitations of current technology and the usual evidential standards have to be met.

Even when evidence is considered sufficient, enforcement policy needs to also be applied proportionately, including education and warning options, as well as staged sanctioning.

Spatial Management

Recent VMS enforcement cases are at the vanguard of policing the growing extent of spatial fisheries regulations. As well as the extension of VMS systems to the inshore fleet, control of fishing in and around marine protected areas is about to get a lot more expansive and complex as measures are progressively rolled out across our seas.

This rollout has yet to be accompanied by aids that will help skippers to navigate the measures. In time, a new initiative by Seafish aims to address this, but as it stands, multiple lists of coordinates in byelaws are all that exist to inform of management boundaries, leaving it to fishermen to enter into their navigation systems in order to make sense of them.

Under these circumstances, the approach to enforcement is critical. Get it wrong and the consequences extend beyond the immediate victims of rough justice. It is likely that many would become wary of entering management areas or making headway at speeds lower than 6 knots, unnecessarily compromising operational freedom and potentially safety. The prospect of heavy legal costs if faced with prosecution may persuade some to plead guilty or accept a fine when given the choice, when in fact they are innocent.

Partnership Building

In contrast to an alienating and remote control form of enforcement is the careful work that has been going on for a number of years between government, scientists and the fishing industry to develop and test bottom-up schemes that seek to involve the industry in tackling some of the more knotty fisheries management challenges.

A good example is the MMO Fully Documented Fisheries Scheme that aids the prevention of unwanted discards, and a similar initiative is ongoing to address unwanted catches of spurdog. These types of collaborative approaches may also provide a relevant model for tackling cetacean and bird bycatch in the future.

The NFFO is an enthusiastic supporter of these collaborative approaches which we believe can demonstrate practical conservation results by working with the grain of maintaining a profitable fishing business and enable industry to get involved and demonstrate responsible marine stewardship.

This requires the building of trust and cooperation between managers and industry, where electronic data gathering and monitoring provides a knowledge base that in turn can facilitate adaptive management approaches. Investment in time and effort is needed on all sides and results may take a number of years to come to fruition as baseline evidence is gathered and trials proved before measures can be applied more widely and benefits realised. This work can then inform how to best frame policy and regulation in order to support best practice.

In an environment that is inherently uncertain and data and knowledge expensive to obtain, giving industry confidence to generate knowledge for the common good should underpin successful fisheries management policy to ensure that management measures are more practical, effective and sustainable.

Culture Clash

Developing a culture of cooperation will not be realised if electronic data is used within a shoot-first-ask-questions-later style of enforcement, leaving it to the courts to do the questioning, and obliging small businesses, even if found innocent, to bear the stress and potentially crippling costs of defending themselves. Such an approach will only serve to generate distrust and an “us and them” culture, persuading industry that it should only ever give the minimum information away and be continually looking over the shoulder so not to fall foul of the authorities. Trust built up can be easily lost.

Getting to grips with how electronic monitoring data on fishing activities should be applied alongside other evidence in enforcement actions, and considering what constitutes sufficient evidence in order to justify a particular course of action is essential, and clarity is needed if the cooperative path between industry and managers is to be realised.